Optimal performance improvement is achieved through the right balance of training loads (intensity and volume) and recovery (duration and type of recovery phase). In this post, we’ll outline these connections without too much biochemistry.

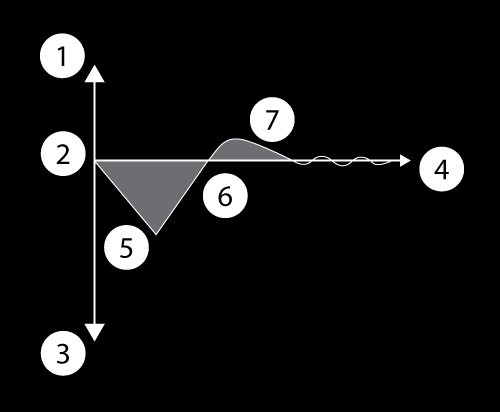

1 = Adaptation (increased performance) 2 = Initial performance level 3 = Fatigue 4 = Training period (days, weeks, months) 5 = Catabolic phase (substrate breakdown); training period (key stimulus for adaptation) 6 = Anabolic phase (substrate buildup); recovery period (regeneration and substrate buildup to the initial level and beyond = supercompensation) 7 = Supercompensation (substrate buildup above the original level)

The simplified model above is based on the “principle of biological adaptation” (supercompensation*). It posits that our body perceives every planned or unplanned load (5) that exceeds a critical threshold as a disruption of equilibrium, resulting in a temporary decrease in performance (2/3). During the recovery phase (6), the body not only returns to its previous state but supercompensates (7), preparing itself for the next load. This leads to performance improvement – adaptation.

For example, after an intense endurance session (e.g., 30 minutes of jogging), the glycogen stores in the muscles are depleted. During recovery (usually 2-3 days), they are refilled above their previous levels. The supercompensation model also applies to strength training (e.g., in hypertrophy training), where adaptations (muscle growth) occur in the targeted muscle groups. The adaptation process is still not fully understood and remains a topic of research (see below).

To achieve biological adaptation and improved performance, an optimal balance of training and recovery phases is necessary.

Loads above the threshold lead to fatigue (e.g., due to muscle acidification from lactate), often resulting in reduced performance. If you feel weak continuously and your performance plateaus, it’s time for a break.

Recovery after a training session can be passive (“waiting” for recovery, possibly aided by massage, sauna, sleep) or active (e.g., light exercise, gentle jogging). Switching to different muscle groups also counts as active recovery. A combination of active and passive measures is ideal.

If the recovery phase between training sessions is too long, the training effect is lost. This is why we encourage our athletes to train consistently. Rest weeks are also part of training and can include light endurance sessions, yoga, etc.

The balance between load and recovery applies to individual training sessions but can also refer to larger periods like weeks or months.

Examples:

- Strength training: the body adapts with increased protein synthesis (about two days), which leads to an increase in muscle fiber cross-section (approximately 4-6 weeks). The hypertrophied muscle cell is thus better prepared for future strength demands.

- Endurance training: the body responds primarily by increasing glycogen stores (about 2-3 weeks), increasing and expanding mitochondria, and improving capillarization. This creates favorable conditions for aerobic energy production during subsequent exercise.

The recovery time depends on the primary energy source used during training.

The best time to apply a new training stimulus is during the supercompensation phase. The timing can vary significantly; after an extreme load (such as a marathon or a weightlifting competition), recovery may take several weeks. When fully recovered (supercompensation), the body can deliver greater performance than before.

Criticism of the supercompensation model

The different body systems require very different recovery times. Additionally, training involves not only biological processes according to the supercompensation principle but also learning processes.

The more complex the target movement, the more demanding the learning process. The learning curve, however, is not a supercompensation curve but rather levels off toward a learning plateau.

The supercompensation principle should be understood as a model that generally outlines the requirements for training design over time. We coaches set parameters like intensity, load duration, rest duration, and training cycles in our macro training plan and break them down into individual sessions.

You should also focus on a balanced diet (drink plenty of water) and adequate sleep – and, of course, attend training regularly and listen to your body and your coaches. :-) Let us know if anything feels off; there are plenty of ways to be heroic – it’s not necessary in training.

In the follow-up post “How often should I train?”, we address CrossFit training frequency and what’s optimal for each level.

*The “supercompensation model” is based on research by Yakovlev (1977) on muscle and liver glycogen after exercise in animals (Nikolaj Nikolaevich Yakovlev: Sport Biochemistry. Barth, Leipzig 1977. Also: Sports Medical Series of the German University of Physical Culture. Leipzig 1977, Vol. 14)